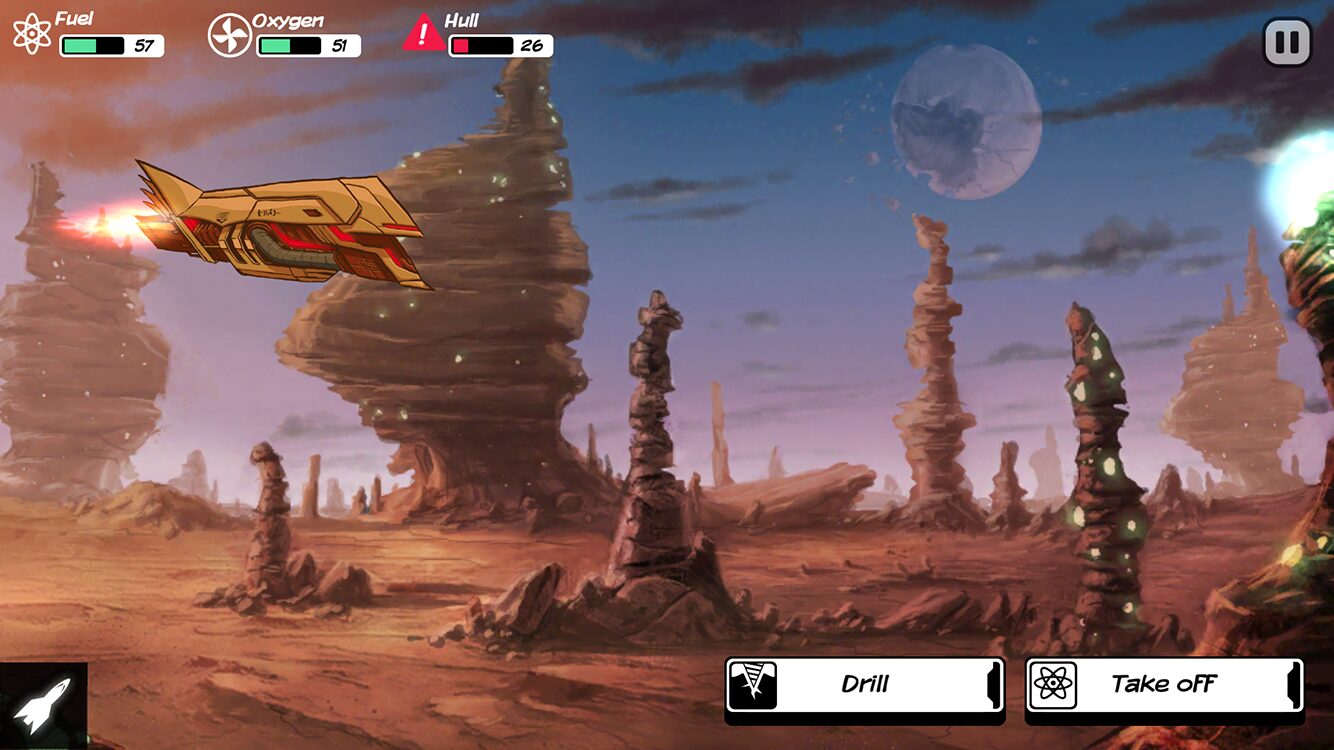

Cargo is mostly made up of elements gathered from planets – the important ones are hydrogen and helium (for refilling your ship’s fuel), oxygen (for refilling your ship’s oxygen (duh)) and iron (for repairing your ship’s hull).

Equipment is stuff you need to move the ship around (thrusters and hyperdrives), tools for harvesting resources and devices that provide useful informational enhancements to the various menus.

Out There’s storage system is more simplistic: you have a set number of slots, and each slot can contain either equipment or cargo. Often you have to make choices about what equipment and cargo to keep and what to throw away, but usually the considerations made are purely monetary – you throw away the stuff that’s worth less money, you replace your various ship parts with more expensive variants, and generally you optimise for asset value at end-game. In Weird Worlds you have a certain amount of space for cargo (artefacts and such), and a set number of slots for equipment (thrusters, weapons, informational modules and that sort of thing) with which to enhance your ship (or fleet)’s capabilities. The only aliens the player meets are completely non-humanoid and speak in an incomprehensible babble, and ship-to-ship dogfights are never an option, as the astronaut’s ship is equipped with no weapons.īoth Out There and Weird Worlds have some concept of spaceship storage space – a common feature across space sims. Whereas Weird Worlds presents the player with an eccentric Hitch Hiker’s-flavoured universe and the task of embarking on a well-funded but time-limited voyage of discovery, meeting, trading with and fighting aliens they meet on the way, Out There casts the player in the role of a hopelessly lost human astronaut with the ever-depleting resources of fuel, oxygen and ship hull integrity, all of which must somehow kept above zero for as long as it takes the astronaut to find their way home. But that’s about where the similarities end. Out There Ω is yet another take on the genre, most similar to Weird Worlds in that (a) doing things in the game is very much an abstracted process dealing with menus and making numbers change and (b) some effort has been made to construct a narrative around the experience.

#Out there omega edition alien simulator#

Another, freeware example of the genre is Yahtzee Croshaw’s Adventures in the Galaxy of Fantabulous Wonderment, which combined space simulator resource management and turn-based ship combat with a straight-forward, linear point-and-click adventure game narrative, puzzles included.

In Flatspace, you physically fly your ship around space, chasing asteroids with your tractor beams, firing lasers and missiles at enemies and initiating docking procedures with space stations in Weird Worlds, things are more abstract, and you mostly navigate through menus, interacting on the level of solar systems rather than individual ships, and playing very short games exploring randomly generated galaxies rather than piloting one ship in one game world for hours on end. Unlike many other genres of games, the actual gameplay implementation of a space simulator is extremely variable. In all of these games, you pilot a spaceship and fly around the galaxy/universe doing whatever you want: exploring, fighting other ships, trading resources, and so on. Two of the first games I ever bought online were Flatspace and Weird Worlds: Return to Infinite Space 1, two very different interpretations of the idea that started with Elite in 1984. I have a special fondness for space simulators.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)